Poems written in Valais

The Valais landscape played its part in a fruitful period of completion for Rilke.

“[…]as I experience it, the Wallis [Valais] seems to me not only one of the most glorious landscapes I have every seen, but also capaible in grandiose fashion of offering manifold equivalents and correspondences to the expression of our inner world […]

Rilke to Xaver von Moos, March 2, 1922.

(Trans. by Jane Bannard Greene & M.D. Herter Norton, Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke Vol. II. Yale UP: 1947.)

From the 7th through the 26th of February 1922, Rilke was seized with unparalleled creative elan. Within a few days, the poet wrote four new elegies and finished two others. The Duino cycle will consist of ten elegies in total when it is finished. At the same time, between February 2nd and 23rd, he composed a cycle of 55 poems hardly less important than the elegies, Die Sonette an Orpheus. Both works were published in 1923.

“Enough. They are here.

I went out into the cold moonlight and stroked the little tower of Muzot as if it were a large animal – the ancient walls that granted this to me. And the ruined Duino.

The whole shall be called:

The Duino Elegies.

They will get used to the name. I think.”Rilke to his publisher Anton Kippenberg, February 9, 1922.

(Trans. by Stephen Mitchell in Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus. Ed. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Vintage International, 2009, xviii.)

“In just a few days, it was a nameless storm, a hurricane in the spirit (like that time at Duino), all that was fiber in me and fabric cracked – eating was not to be thought of, God knows who fed me.

But now it is. Is. Is.

Amen.”Rilke to Marie von Thurn und Taxis, February 11, 1922.

(Trans. by Jane Bannard Greene & M.D. Herter Norton, Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke Vol. II. Yale UP: 1947.)

“At last! The Elegies are here, they exist. […] Dear friend, now I can breathe again and, calmly, go on to something manageable. For this was larger than life – during these days and nights I have howled as I did that time in Duino – but, even after that struggle there, I didn’t know that such a storm out of mind and heart could come over a person! That one has endured it! That one has endured.”

Rilke to Anton Kippenberg, Februrary 9, 1922.

(Trans. by Stephen Mitchell in Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus. Ed. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Vintage International, 2009, xviii.)

From February 12-15, 1922, in the midst of the work on the elegies and sonnets, Rilke also wrote Letter to a Young Poet. It emerged from a prose sketch, “Erinnerungen an Verhaeren,” whose title references the Belgian poet Verhaeren, with whom Rilke was friends.

The Duino Elegies

From the Ninth Elegy:

“Praise this world to the angel, not the unsayable one,

you can’t impress him with glorious emotion; in the universe

where he feels more powerfully, you are a novice. So show

him

something simple which, formed over generations,

lives as our own, near our hand and within our gaze.

tell him of Things. He will stand astonished; as you stood

by the rope-maker in Rome or the potter along the Nile.

Show him how happy a Thing can be, how innocent and ours,

how even lamenting grief purely decides to take form,

serves as a Thing, or dies into a Thing–, and blissfully

escapes far beyond the violin.—And these Things

which live by perishing, know you are praising them;

transient,

they look to us for deliverance: us, the most transient of all.

They want us to change them, utterly, in our invisible heart,

within – oh endlessly – within us! Whoever we may be at last.(Trans. by Stephen Mitchell in Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus. Ed. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Vintage International, 2009, pp. 57-59.)

The Sonnets to Orpheus

In Muzot, Rilke went through his correspondence and wrote in this context to a friend in Munich, Gertrud Ouckama Knoop, whose daughter Wera, a talented dancer and musician, died of leukemia at 19. Rilke asked her mother to send him an object dear to Wera. In response, Gertrud Ouckama Knoop sent him sketches she had written about the illness and death of her daughter. Reading these pages became an important catalyst for the creation of the Sonnets to Orpheus.

“In a few days of spontaneous emotion, when I actually intended to take up some other work, these sonnets were given to me.

You will understand at first glance why it is that you must be the first to possess them. For, undefined as the relation is (only a single sonnet, the next to last, XXVth, calls Vera’s own figure in to this excitation dedicated to her), it dominates and moves the course of the whole and penetrated more and more although so secretly that I recognized it only gradually this irresistible creation that so staggered me.”Rilke to Gertrud Ouckama Knoop, February 7, 1922.

(Trans. by Jane Bannard Greene & M.D. Herter Norton, Letters of Rainer Maria Rilke Vol. II. Yale UP: 1947)

Sonnet 25

But you now, dear girl, whom I loved like a flower whose name

I didn’t know, you who so early were taken away:

I will once more call up your image and show it to them,

beautiful companion of the unsubduable cry.Dancer whose body filled with your hesitant fate,

pausing, as though your young flesh had been cast in bronze;

grieving and listening–. Then, from the high dominions,

unearthly music fell into your altered heart.Already possessed by shadows, with illness near,

your blood flowed darkly; yet, though for a moment suspicious,

it burst out into the natural pulses of spring.Again and again interrupted by downfall and darkness,

earthly, it gleamed. Till, after a terrible pounding,

it entered the inconsolably open door.(Trans. by Stephen Mitchell in Duino Elegies and The Sonnets to Orpheus. Ed. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Vintage International, 2009, p. 131.)

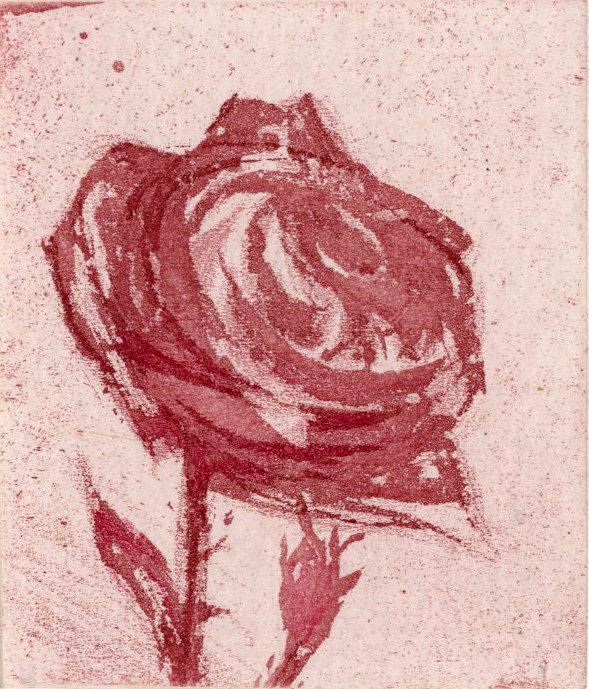

Les Quatrains Valaisans, Vergers, Les Roses, Les Fenêtres 1924-1927

Poems in a borrowed language (“langue prêtée”).

For a long while, Rilke’s poem cycles in French, created after the deluge of the Duino Elegies and in the aftermath of the Sonnets to Orpheus, were seen as nothing more than some light linguistic play. They were received as bucolic genre poems, a sort of tranquil poetic recovery. This is only one aspect of the work, however, as is the poet’s gratitude to the landscape that “made possible” the completion of the Elegies and Sonnets.

Rilke had always felt a deep-reaching and constitutive connection to his surroundings. He learned to speak multiple languages, read others, and translated some into German. In these poems, language – in this case French – joins Rilke’s appropriation of the spatial & visual and his concern with the continuing influence of the past as a connecting link. Language becomes the medium and mediator of (re)unification (what Rilke refers to as “Einswerdung”). The language of these poems, like the Rhone, connects the Valaisan landscape with France – and therefore with Paris and Rilke’s pre-war period as well. This connection, for Rilke, is profoundly healing (“wiederanheiland”). In this ‘new’ language, the use of which has something playful and rejuvenating about it, the poet seizes new territory both thematically and poetically.

Exemplary work in French

Les Quatrains Valaisans

VI

Pays silencieux dont les prophètes se taisent,

pays qui prépare son vin;

où les collines sentent encore la Genèse

et ne craignent pas la fin!

[…] Pays dont les eaux sont presque les seules nouvelles,

toutes ces eaux qui se donnent,

mettant partout la clarté de leurs voyelles

entre tes dures consonnes.

XXXI

Chemins qui ne mènent nulle part

entre deux prés,

que l’on dirait avec art

de leur but détournés,chemins qui souvent n’ont

devant eux rien d’autre en face

que le pur espace

et la saison.

Vergers

XVIII

Eau qui se presse, qui court –, eau oublieuse

que la distraite terre boit,

hésite un petit instant dans ma main creuse,

souviens-toi!Clair et rapide amour, indifférence,

presque absence qui court,

entre ton trop d’arrivée et ton trop de partance

tremble un peu de séjour.

Les Fenêtres

III

N’es-tu pas notre géométrie,

fenêtre, très simple forme

qui sans effort circonscris

notre vie énorme?Celle qu’on aime n’est jamais plus belle

que lorsqu’on la voit apparaître

encadrée de toi; c’est, ô fenêtre,

que tu la rends presque éternelle.Tous les hasards sont abolis. L’être

se tient au milieu de l’amour,

avec ce peu d’espace autour

dont on est maître.

Rilke as translator

After the elegies were finished, Rilke focused on both his poems in French and the Valéry translation. Rilke felt connected with France and frequently emphasized how important Valéry’s poetry was for him. He admired the French poet deeply, both for the exact conceptions of his poems and his sophisticated sensuality. His translations are unsurpassed. In 1921, he translated the poem Le cimetière marin. Between 1921 and 1923, he translated 23 poems from Charmes, which were published in 1925 under the title Paul Valéry, Gedichte (Poems). In 1924 and 1926, he completed translations of the prose dialogues Eupalinos ou l’Architecte and L’âme et la danse. He followed these between the 15th and the 27th of October 1926 with Tante Berthe. Rilke valued his German translations of Valéry’s poems more highly than his own poetry in French. Valéry could not read Rilke’s German texts, but published a few of Rilke’s French poems as “échantillons modestes” (“several modest attempts”) in November 1924 in the journal Commerce.

Monique Saint-Hélier describes Rilke’s admiration for Valéry with an enthusiasm that matches the poet’s own:

“Rilke may have loved and admired Valéry more deeply than anyone else in the world. ‘I was alone,’ he said later, ‘I was waiting, my entire work was waiting. One day I read Valéry – I knew that my waiting was at an end.’ Rilke drew all of what was valuable from this work – its gold, frankincense, and myrrh. He poured over it with love, patience, tenderness. In the stillness of Muzot, in the hushed hours of that Valaisan tower, Valéry’s verses were weighed upon the scales of a time that does not err, an inner quiet that speaks the truth. No one has yet paged through Valéry’s poems with more enamoured soul or angelic hands. And no one has agreed with him more unequivocally. Rilke did not translate Valéry’s poems – his love transcended mere translation. The vital will he brought to the work created it anew. This was not translation, this was osmosis, a blood transfusion.”

Monique Saint-Hélier, À Rilke pour Noël. Bern 1927 (orig. French).